DAO LAW- BASED-TO-ETHEREUM

In 1977, Wyoming invented the LLC, which protects entrepreneurs and limits their liability. More recently, they pioneered the DAO law that establishes legal status for DAOs. Currently Wyoming, Vermont, and the Virgin Islands have DAO laws in some form.

A famous example:

CityDAO – CityDAO used Wyoming's DAO law to buy 40 acres of land near Yellowstone National Park.

Buterin, in the Ethereum white paper (Ethereum, 2013, p. 23), defines a DAO as a “virtual entity that has a certain set of members or shareholders which [...] have the right to spend the entity's funds and modify its code”. That is, the aim is to replicate “the legal trappings of a traditional company or nonprofit but using only cryptographic blockchain technology for enforcement” (ibid).

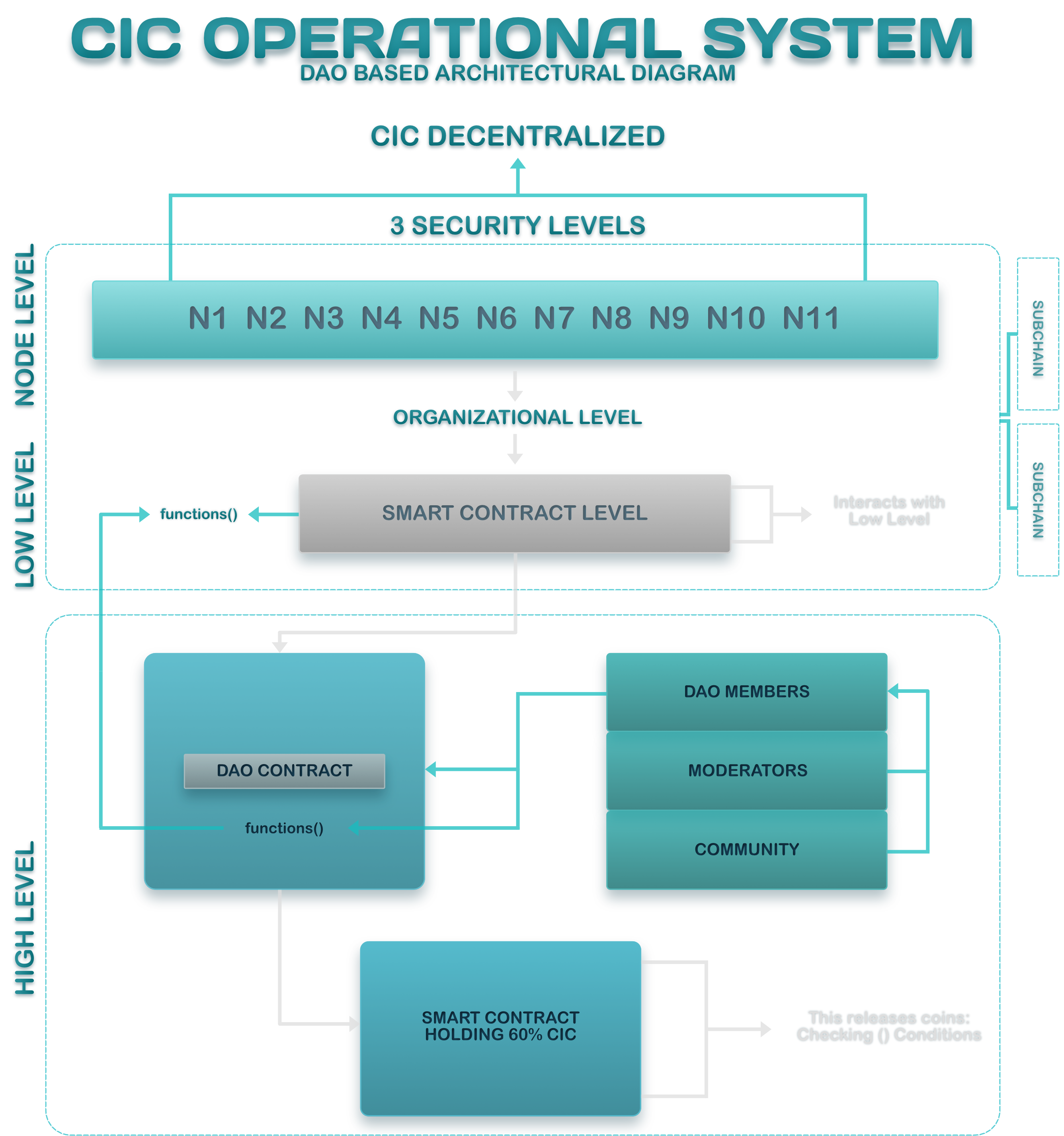

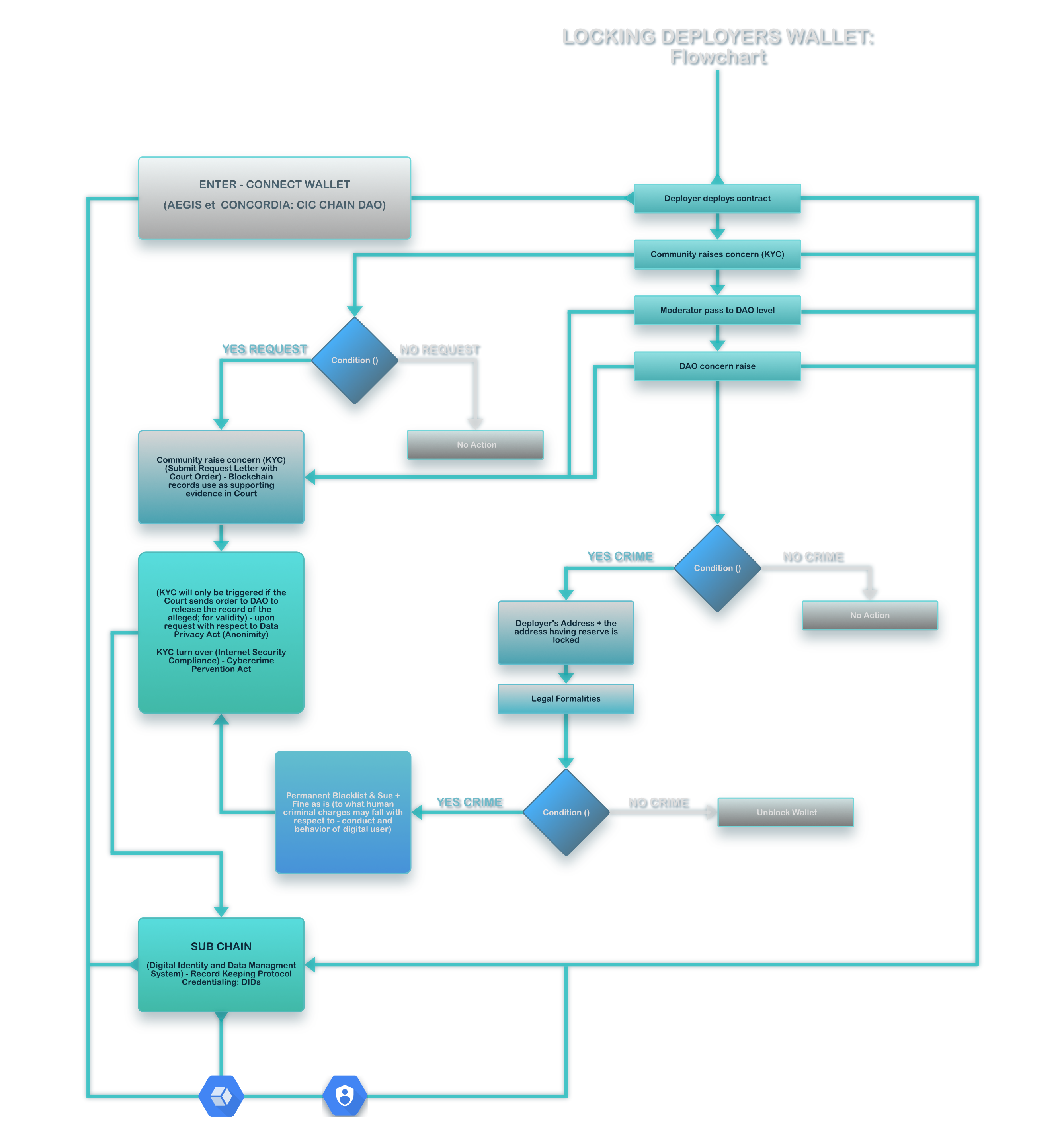

HENCE, CIC BLOCKCHAIN TECHNOLOGY DAO “AEGIS ET CONCORDIA” adhere the policy of Ethereum: legal replication but only using cryptographic blockchain technology for enforcement; all concerns must be directed to the technology used to have an immutability of records other medium used to address the concerns will not be honored, as is , for CIC DAO is within the realm of SUBSTANTIVE and NATURAL Law governing a privilege rights to serve humanity and promote peace and harmony in the lives of the users of the technology.

Sources:

https://ethereum.org/en/dao/

|

https://www.citydao.io/

GUIDELINES AND POLICIES

CIC DAO is based from the following studies:

The distinctive features of blockchain-based systems have led key stakeholders in the blockchain space to describe public, permissionless blockchains as “alegal” systems. This term was introduced in the blockchain space by Ethereum co-founder Gavin Wood (2014) to advance the idea that decentralized blockchain-based systems are similar to forces of nature (Lustig, 2019): they are neither legal nor illegal; they merely subsist outside of the legal realm. The claim made by these commentators is not that blockchain-based platforms are difficult to regulate (as the argument was with regard to the Internet in its early days) but rather that they should be regarded as neither an object nor a subject of law (Atzori, 2015). Indeed, to the extent that they do not depend on a single centrally controlled web interface and no physical assets are involved in any of the associated transactions, these platforms can be designed to largely ignore the coercion of the law (Miller, 2019): not only do they not depend on the coercive force of the State to enforce transactions and commitments but they are also indifferent about the legal context in which transactions and commitments occur.

INTERNET SECURITY (EU GDPR)